There’s a reason these epicenters are referred to as "concrete jungles." Some of the most populated American cities are inundated with physical structures. New York City may at first glance appear to be an outlier because it boasts one of the most famous urban parks in the world, Central Park, but in reality, the difference in raised structures versus parks is striking: The Big Apple has an estimated 1 million buildings, and only 1,700 parks and other recreational facilities.

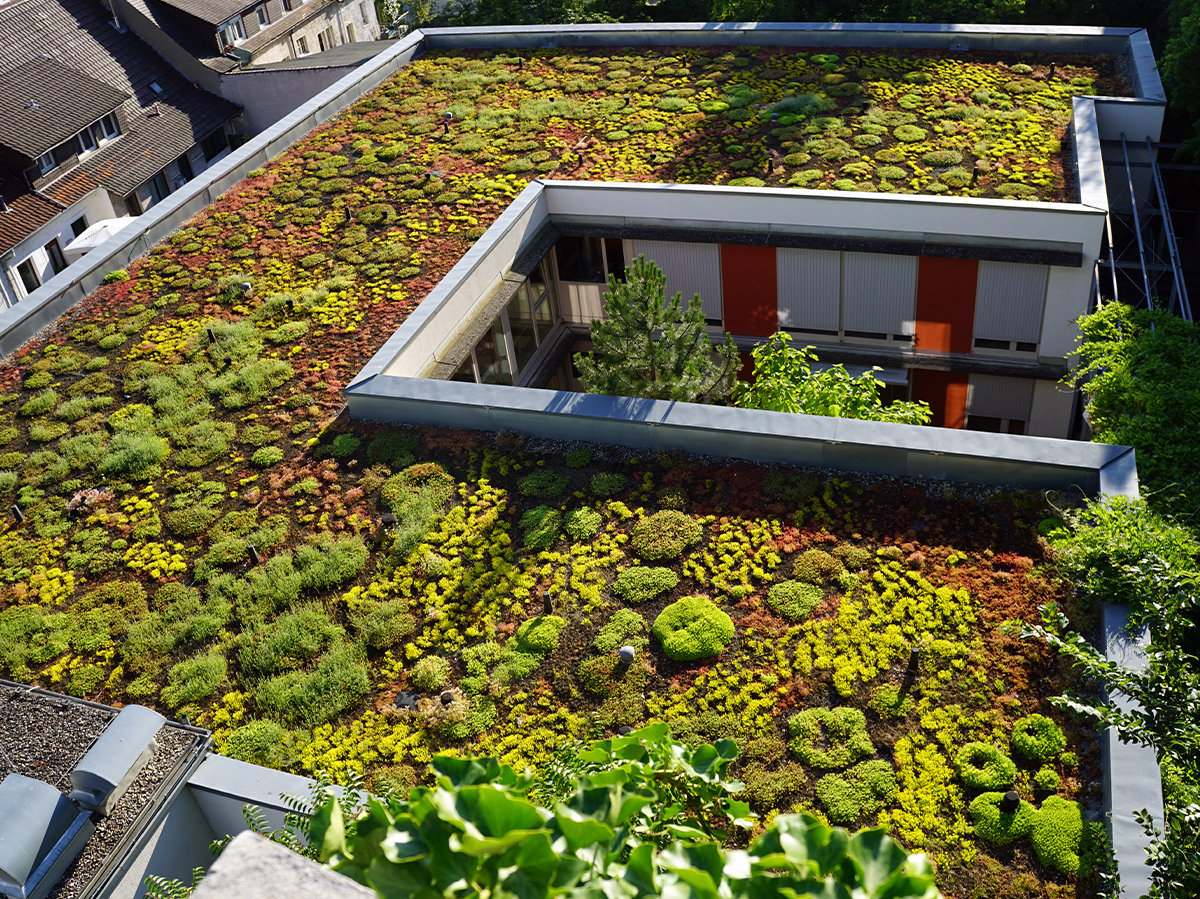

While New York City is currently undergoing a veritable parkland revolution, an entirely new concept is redefining how green spaces are utilized within otherwise flora-starved metropolises. Although largely unnoticeable from street level, public and private sector buildings are increasingly incorporating green roofs on conventional rooftops to reflect sunlight and absorb rainwater.

As governments are confronted more and more with the harsh realities of an ever-warming planet, green roofs are becoming all the rage. It’s not only municipalities interested in transforming existing roofs, either. Private enterprises, including real estate developers, are considering green roofs to broaden the appeal of office or living spaces and maximize their ancillary environmental and cost-saving benefits.

For those in the industry, the grass may only get greener from here. Green Roof for Healthy Cities, a nonprofit green roof trade association, reports the industry grew by 10 percent from 2015 to 2016. According to its survey, Toronto and Chicago led the continent in 2016 with the addition of more than 600,000-square feet of green roofing, followed by Washington, D.C., Seattle and Philadelphia.

Green roofs transform sun-drenched rooftops into ecological oases that help reduce the so-called “Heat Island Effect” plaguing congested areas, by cooling the surrounding air. These living, breathing roofs are also known to reduce energy costs, among myriad other benefits, in addition to their aesthetic appeal.

There’s no question that city parks offer much-needed escapes for residents looking to beat the heat. Yet what if the building you work or live in could bring greenery, and all its associated benefits, to you? What if such green spaces could be part of the solution for cities looking to address rising temperatures and air pollution, as well as improve the quality of life?

That’s exactly what’s happening across the country, albeit a little later than in several nations across the Atlantic.

The modern history of vegetated roofscapes dates back to the mid-20th century, as European countries foresaw the advantages of adding greenery to existing rooftops. In the 1970s, Germany realized the impact of green roofing on lessening the burden on storm drains. As technology evolved and agricultural architecture became fine-tuned, the many extraordinary and positive effects of installing a green roof become clearer and clearer by the day.

New York City, which has more than 1.6 billion-square feet of rooftop, is among a growing number of cities considering inventive ways to be more energy efficient and reduce carbon emissions. Although NYC lags behind Chicago and Canadian cities, it has identified green roofs and solar panels as critical keys to increasing sustainability. To that point, three-quarters of New York’s carbon emissions originate from “homes, schools, workplaces, stores, and public facilities,” according to the city.

The Big Apple was also one of the first cities in the United States that pledged to adopt the principles of the historic Paris climate accord after the Trump administration announced it would back out. One of its goals is for the city to become carbon neutral by 2050. Among the ways it intends to accomplish this is by investing in green roofs.

Design and construction varies, depending on the pre-existing roof and local climate. Still, a growing body of research appears to support an industry-wide belief that green roofs are reliable and smart alternatives to the way roofs have been built for decades.

Paul Mankiewicz, a biologist and plant scientist who is the executive director of the Bronx-based nonprofit Gaia Institute, said if New York City, in particular, transformed a small fraction of asphalt rooftops into green roofs, there’d be a noticeable “local dropping in temperature.”

Meanwhile, there are other benefits that often get overshadowed, such as increasing the lifespan of roof membranes—systems designed to move water off its surface—boosting the natural habitat, and leveraging green spaces for educational and agricultural purposes.

“When you see a rooftop, it’s kind of getting to the point where, why wouldn’t you have a green roof?” said Eric Dalski, founder and partner of Highview Creations, which designs and builds green roofs in the New York City region.

Dalski singled out the High Line, a converted railroad trestle and one of the most-trafficked public spaces in Manhattan, as the most famous example. Not only has the elevated park introduced visitors to plant species they'd otherwise never interact with across such a sprawling city, he credited the rise in real estate values to its appeal, too.

“It just shows to prove that people appreciate green space,” Dalski said.

He may have a point. Currently, more buildings—both public and private—are being celebrated for their green roof installations, including Seattle City Hall and the famed Getty Center in Los Angeles.

It doesn’t end there for these gardens in the sky. From brand new high rises and municipal buildings to apartments and public schools, green roofs are now a top priority for urban planners. With scientists blaming three consecutive years of record heat on climate change, and more and more cities confronting the many threats posed by an ever-warming planet, green roofs have been taking on a much more urgent role.

What follows is a comprehensive explainer that defines what exactly a green roof is, breaks down their many key benefits, outlines how they’re used to combat carbon emissions and other pollutants, and examines other reasons why the public and private sector are increasingly incorporating such roofs into urban areas where they live and work.

Back To Top